Elaine Canning sheds light on the role and motivations of Welsh volunteers who took up arms in Spain during the Civil War

In his recollections and re-imaginings of the Spanish Civil War, eighty-eight-year old Belfast man Michael Doherty, the main protagonist of The Sandstone City, remembers a Welsh volunteer from the mining valleys: ‘We’ve befriended a Welsh man, Morris Williams, from the Rhondda, who looks like he’s more cut out for this than us. Must be all that graft in the mines. Morris is a true gent, no question about it’.

Indeed, it was a fascination with the experiences of volunteers from Ireland who fought on both sides of the conflict in the Spanish Civil War that served as one of the primary inspirations for my debut novel.

Once the research was underway, however, and with access to the extensive Spanish Civil War collection at the South Wales Miners’ Library, the broader impact of the war, particularly on those who fought as part of the International Brigades, became apparent.

The Sandstone City is, in part, a reflection on how war and trauma simultaneously shape and fracture an individual, as well as how memories are shelved, resurrected and reconstructed.

And so it was that Irish men and Welsh men, amongst other nationalities, came to the International Brigade headquarters of Albacete in Castile-La Mancha

Whilst Williams, like Doherty himself, is a purely fictional character, he is inspired by the fusion of voices of real men from Wales who volunteered to join Spain’s fight for democracy against fascism during the Civil War of 1936-1939. Indeed, the first Welshman to arrive in Spain in November 1936 was W.J. Davies, an unemployed Tonypandy miner living in London (Francis, 1984). In You are Legend: the Welsh Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War, Graham Davies asserts that the Appendix ‘[…] lists almost 200 ‘Welsh’ volunteers of whom approximately 70 per cent were members of the Communist Party, and more than half were miners’. In the Appendix itself, Davies adds that the lists are of those ‘[…] who served on the Republican side for Spain for whom I found a recognisable footprint […] No doubt there are many others about whom nothing is known, and I have found the names of some who fall into that category’.

The employment background of Welsh volunteers, as well as their motivations for supporting Spain’s Republican government, align with those of other volunteers originating from Britain. According to Antony Beevor, nearly 35,000 foreigners served in the International Brigades during the course of the civil war, with the British constituting just over 2,000; and almost 80 per cent of the volunteers from Great Britain were manual workers who either left their jobs or were unemployed. Moreover, slightly over half of them were Communist Party members.

In Ireland, the situation was quite different, not least because the majority of men who left to fight in Spain did so in support of General Francisco Franco and the Nationalists. Under the leadership of Eoin O’Duffy, the Spanish Civil War was presented as a Holy Crusade of sorts, an anti-Red campaign, a battle between Christianity and Communism. In Crusade in Spain, O’Duffy refers to his act of writing to the Dublin papers, not to appeal for volunteers: ‘[…] I merely stated the issue at stake as it appeared to me – that General Franco was holding the trenches, not only for Spain, but for Christianity’. Yet potential recruits were being encouraged behind closed doors by priests preaching from pulpits or through sliding confessional box windows. Indeed, when a third group gathered for departure on 27th November 1936 as part of O’Duffy’s Irish Brigade, he writes, ‘[…] the volunteers were presented with Rosaries, Agnus Dei and other religious emblems, the gift of the Right Rev. Monsignor Byrne, Clonmel, Dean of Waterford’.

Gofod i drafod, dadlau, ac ymchwilio.

Cefnogwch brif felin drafod annibynnol Cymru.

According to Robert Stradling, O’Duffy’s antagonist in the Spanish Civil War was Frank Ryan, a soldier who, like O’Duffy himself, was a practising Catholic and a dedicated fighter for Ireland during the wars of independence. Ryan led a smaller contingent of men to Spain, with a profound commitment to democracy and a rejection of international fascism, rather than abandonment of his own faith or religious practice. Ryan claimed that: ‘[…] It is also a reply to the intervention of Irish Fascism in the war against the Spanish republic which, if unchallenged would remain a disgrace on our people’.

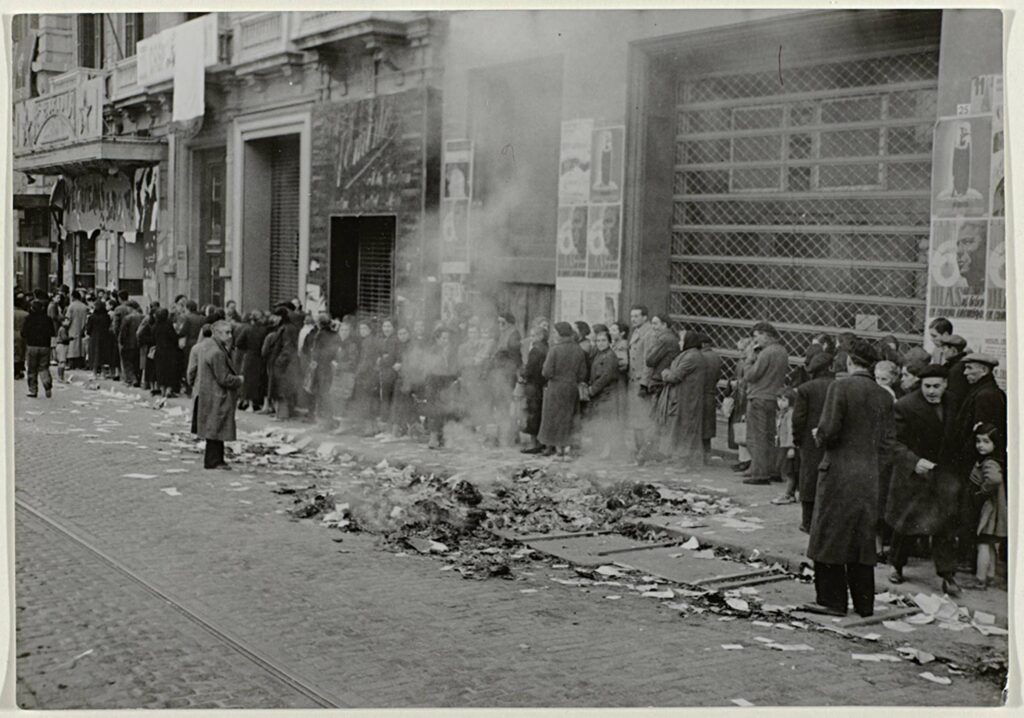

And so it was that Irish men and Welsh men, amongst other nationalities, came to the International Brigade headquarters of Albacete in Castile-La Mancha, more than two hundred kilometres southeast of Madrid. Like their Welsh counterparts, Stradling writes, the majority of men from Ireland who fought for the Spanish republic were ‘working-class men’, though they hailed from ‘[…] the slums of Belfast and Dublin, along with other substantial urban centres like Cork and Waterford’.

The rich repository of letters and testimonies of several Welsh volunteers held at the South Wales Miners’ Library, along with editions of The Volunteer for Liberty, provide invaluable insights into not only responses and reactions to a foreign war against fascism, but also interactions with other nationalities, including Irish men.

In Miners Against Fascism, Hywel Francis has included numerous letters from more than a dozen Welsh miners writing to family, friends and more formal acquaintances. These letters reveal varying degrees of hope and hopelessness in wartime, of preoccupations with shortages of foodstuffs, such as milk and butter, as well as manifestations of pride in battle and grief for fallen comrades.

‘There are no two opinions, happiness for us is only possible when fascism is wiped from the face of the earth.’

The letters are infused with details of suffering, including that of Spanish civilians, young and old, and the breadth of their courage and industry, together with snap shots of contentment and satisfaction. In some cases, the latter stems from victory over the Nationalists, albeit short lived, to gratitude for natural heat, light and a decent meal in an abandoned church. Writing to his mother, for example, Sam Morris tells her: ‘We have been travelling for many days now in Spain, there is continual sunshine here the weather being splendid, we find the Spanish people very sociable, […]’ (qtd in Francis). Jim Brewer, on the other hand, writes to his parents with a more sobering message: ‘I did the right thing in coming here. There are no two opinions, happiness for us is only possible when fascism is wiped from the face of the earth. It wasn’t any spirit of adventure that sent me here’ (qtd in Francis). These are men who oscillate between outbursts for simple things such as Woodbine cigarettes, books, socks and photos, to quiet, shrunken shadows of their former selves disturbed by the sight and smell of death and fear of returning home.

Yet not all their (hi)stories have yet been shared. The South Wales Miners’ Library also houses a number of unpublished memoirs from several of the volunteers who served in Spain. Those memoirs, which form the basis of a new project currently underway with Sian Williams, Head of the South Wales Miners’ Library, highlight what it meant to be a fighter and prisoner during the Spanish Civil War, together with survival mechanisms in the face of regular brushes with brutality, deprivation and suffering. In fact, they also shine a significant light on the value of comradeship, whatever form circumstances might have allowed it to take, amongst the dregs of burnt-out cigarettes and permanent scars.

The Sandstone City is an attempt to capture just a fraction of those experiences through Michael Doherty, his comrades and ghosts: those scarred, bruised, fictional embodiments of camaraderie and resilience buried within the novel’s pages.

The Sandstone City by Elaine Canning is out now with Aderyn Press and can be purchased from your local bookshop or from the publisher’s website (£8.99 in paperback):

Works Cited

Beevor, Antony ([1982] 1999), The Spanish Civil War, London: Cassell.

Canning, E. (2022), The Sandstone City, Aderyn Press.

Davies, G. (2018), You are Legend: the Welsh Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War, Cardiff: Welsh Academic Press.

Francis, H. (1984), Miners Against Fascism: Wales and the Spanish Civil War, London: Lawrence and Wishart.

O’Duffy, E. ([1938] 2019), Crusade in Spain, Reconquista Press.

Stradling, R.A. (1999), The Irish and the Spanish Civil War 1936-39, Manchester, Mandolin.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.