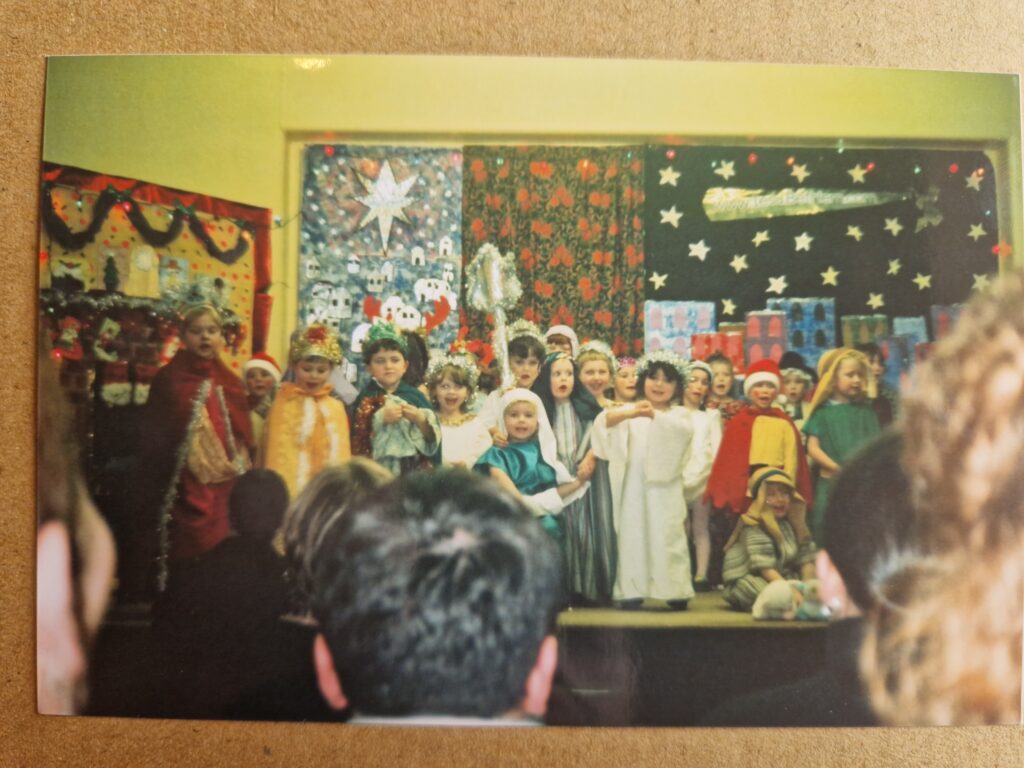

Rebecca Wilson reflects on why Mrs Roberts Dre failed to cast her, a real Jew, as Mary in Ysgol Cwm-y-Glo’s nativity play.

2001. Sideways rain slams against the kitchen window. I sit at the table, my back against the radiator, slipping my freezing feet from the harsh slate slabs into my fluffy red Teletubbies slippers. I am attempting to accept my first acting rejection. I am 4 years old.

My Mum blesses the Shabbat candles. My Dad blesses the Challah bread. We eat too much, and my sister tells me i stopio bod mor dramatic.

But this was my first rejection. My first failure. I had stumbled at the first hurdle of my acting dream. Mrs Roberts Dre had cast Rebecca Parry as Mary and not me. She had chosen not to cast a real Jewish girl, an opportunity that wasn’t likely to arise again soon in the small Welsh village of Cwm-y-Glo.

And although I’ve since had my ego boosted and dreams met, having worked professionally as an actor for the National Theatre, I should be over it… but I’m not. And I want to know why.

Why didn’t I fit in? Why wasn’t I part of the story? Part of a traditional tale that so much of the country’s fundamental values are supposedly built on. That so much of my Welshness is a part of. I was excluded from the storytelling.

And perhaps like my sister you think I’m being dramatic. But storytelling forms our identity. And this was my introduction.

Being Welsh is often synonymous with Christianity and especially within the Welsh language. The first printed book in the Welsh language was by John Price in 1546 and alongside the Welsh alphabet and instructions on how to read, it included the Lord’s Prayer and articles about the Catholic faith. Then in 1580 the first book printed in Wales itself was called Y Drych Christnogol which translates as The Christian Mirror, attempting to convince the people of Wales to remain Catholic and not to convert to the Church of England.

As my Jewish identity developed over in England, it felt very separate to the life I was living in Wales.

Wales has a unique relationship with using Christianity as a storytelling tool in order to engage – and specifically in teaching people how to read. During the 18th century Griffith Jones, a Welsh priest, created a travelling school which he took around the whole of Wales, using the bible to teach reading and helping Wales become one of the most literate countries in Europe at that time. He apparently reached over 200,000 people. An entire generation learnt to read because of biblical storytelling.

And although this achievement – like many of Wales’ social enterprises – gives me, as a Welsh woman, a great sense of pride, I also cannot ignore the uncomfortable contention I feel as a Jewish woman who grew up living in the Wales Griffith Jones helped to build with his bible.

A few years on from the nativity nightmare, my Mum is trying to decide the best way to introduce her two little Jewish girls to this thing called the Holocaust. She chose to do that through a book too. We read Judith Kerr’s semi-autobiographical novel When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit and a little later The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank. And like many of the little Welsh children before me, I learnt new words, how to read sentences and sounds – but I also learnt what happened to people like me. I learnt that we had to hide because otherwise we’d be killed.

Gofod i drafod, dadlau, ac ymchwilio.

Cefnogwch brif felin drafod annibynnol Cymru.

So, the Holocaust became part of my fabric. I knew there should’ve been six million more Jews in the world – and so my family kept up the traditions, and I proudly kept my identity.

But as my Jewish identity developed over in England, it felt very separate to the life I was living in Wales. A Wales where every Wednesday night Dylan Jones would conduct us in Welsh as I played my cornet in the county brass band in Caernarfon, then somehow through a six-hour car journey of bingeing Gavin & Stacey and munching on KFC, I would enter my other life – where Rabbi Charley Baginski would read Hebrew blessings and tell us her funny sermons at Kingston Liberal Synagogue in celebration of Rosh Hashanah.

And although I felt at home in both of these places, surrounded by family and close friends, other people didn’t see me this way. Strangers didn’t know me. And when they asked, and when they still ask who I am I tell them I’m Welsh and I’m Jewish.

But they don’t see me as both. They see me as one or the other. An anomaly.

I didn’t feel comfortable being Welsh in London and I didn’t feel comfortable being Jewish anywhere.

And because of the long history of both Welsh and Jewish voices being silenced it means that when I’m on a date or being introduced to new people I get the following array of reactions: ‘that’s weird’, ‘I’ve never met someone like you before’, ‘how can you be both?’, ‘you can’t really be Jewish, you haven’t got the nose?’, ‘you don’t sound Welsh?’, ‘does that mean you’re super rich?’, ‘does your Dad have the curls?’, ‘are you circumcised?’, ‘can you date non-Jews?’, ‘you’re only proper Welsh if you speak Welsh’, ‘speak some now’, ‘do you speak Jewish?’ or simply: ‘I don’t like Jews.’

But to me there weren’t differences, I never felt uncomfortable in myself. It was only when I told people my truth it made them feel uncomfortable.

All I could feel were connections. So many pieces of my Welsh fabric and Jewish fabric could be sewn together and constantly made me feel grounded and comfortable. Tiny moments that were just for me. Pronouncing the ch sound. Baruch in Hebrew, chwarae in Welsh. Appreciating nature. Singing the ‘Tree of Life’ in synagogue and being taught to be grateful for them, then really being grateful for the trees during rainy weekend walks in Wales. Blessing Challah bread every Friday at home and blessing Bara Brith every bite.

Praying using Duw instead of God.

But all other people saw was a ‘money-grabbing Jew’ and a ‘sheep-shagger’. Both felt equally shit and both have, in the past, made me feel worthless and like I shouldn’t exist.

And yet, more than two decades on from Mrs Roberts Dre’s casting faux-pas, I’ve realised that while Wales probably wasn’t ready for a real Jew to play Mary, I don’t know if it’s even ready now.

But I exist. My presence as a Welsh Jew is not woke, I’m not ticking a box, I don’t even have a box (that’s another essay for another day). I’m just a person trying to bring kindness and light into the world. In the Jewish faith we call this sentiment Tikkun Olam. When you try to leave the world in a better place than when you found it.

And from all of the communities and artists in Wales I’ve worked with so far, they have an incredible understanding of this.

Let me take you back to 2001. Ysgol Cwm-y-Glo’s nativity. I only remember not being cast as Mary – but according to my Mum I was cast as a star.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer. If you want to support our work tackling Wales’ key challenges, consider becoming a member.