We will see the continued rise of populism unless we ditch the GDP obsession and change tack to wellbeing economics, argues Duncan Fisher

This is the first article in a series exploring why misery drives populism and why moving to wellbeing economics is the answer. You can read the second article here and the third article here.

In a series of four short posts I want to make a case for wellbeing economics to be made the lynchpin of economic policy in Wales, replacing the central pursuit of growth. Wales has already taken a lead with the Well-being of Future Generations Act in 2015, but since then there have been two game-changing events that up the stakes dramatically.

First the Brexit vote of June 2016, which put a spotlight on just how unhappy and alienated so many people in Wales feel. Then the more recent declaration of a climate emergency in Wales – as Greta Thunberg has urged, we now need to panic like our house is on fire.

It is quite evident that fundamental system change is absolutely and urgently required and that there is a long way to go to achieve it but very little time. I believe that shifting to wellbeing economics is fundamental to such system change.

The purpose of these four posts is to float ideas and invite reaction and rapid discussion. The global organisation, Wellbeing Economy Alliance, provides an invaluable resource for discussions everywhere in the world. The Alliance has provided great help to me in composing these posts.

At the end of the series, after assessing the feedback to the first three pieces, I will float ideas for what more we could do in Wales to hasten the journey towards system change. The Wellbeing Economy Alliance stands by ready to help, connecting us with the best minds and activists across the world.

Misery drives populism

The unhappiness revealed in Wales by the Brexit vote is a major political threat to the country.

At a remarkable wellbeing economics seminar at the London School of Economics in January this year, Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, Professor of Economics and Strategy at Oxford University, presented disturbing new evidence on the relationship between misery and populism.

Globally measures of stress, pain and anxiety are increasing, despite constant economic growth, and the correlations of these measures with populism and civil unrest are striking.

In research soon to be published, a remarkable correlation emerges between Trump voting by region and unhappiness, as measured in daily polls by Gallup. Nothing found so far correlates so well with Trump voting.

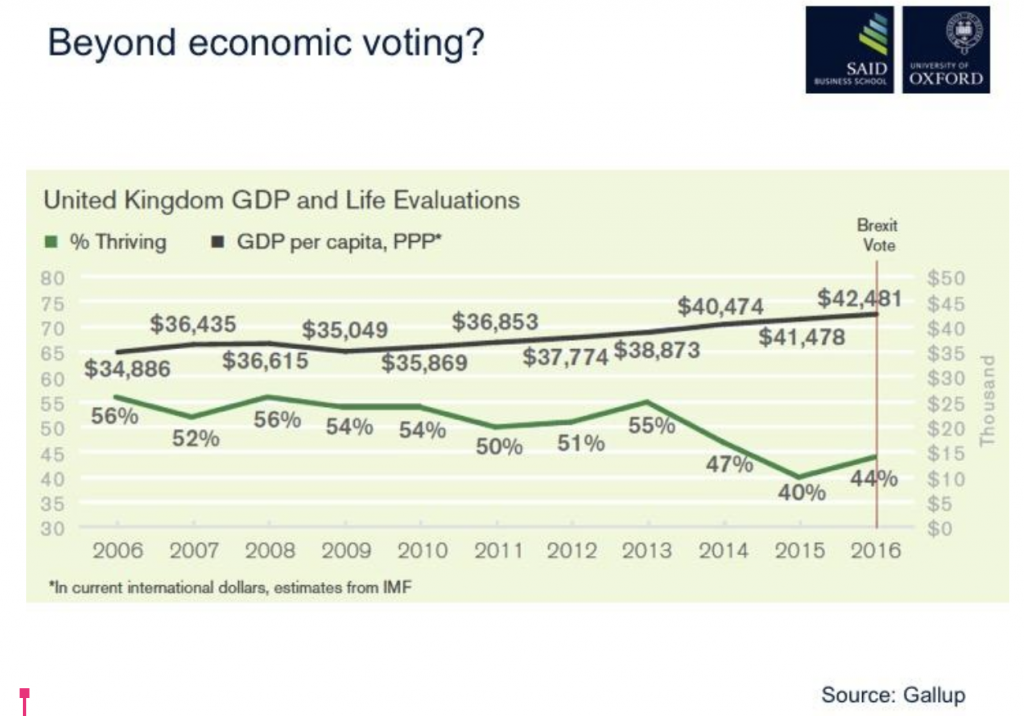

Here in the UK, Brexit was preceded by an extended period of increasing misery, again despite economic growth during the whole period.

A key predictor of misery is job insecurity. Professor De Neve suggested that the considerably higher happiness scores in Scandinavia compared to the USA, despite high GDP in both places, is greater job security in Scandinavia. Job protection in Scandinavia is in striking contrast to the hire and fire, boom and bust approach that is so much stronger in USA. Volatility hurts.

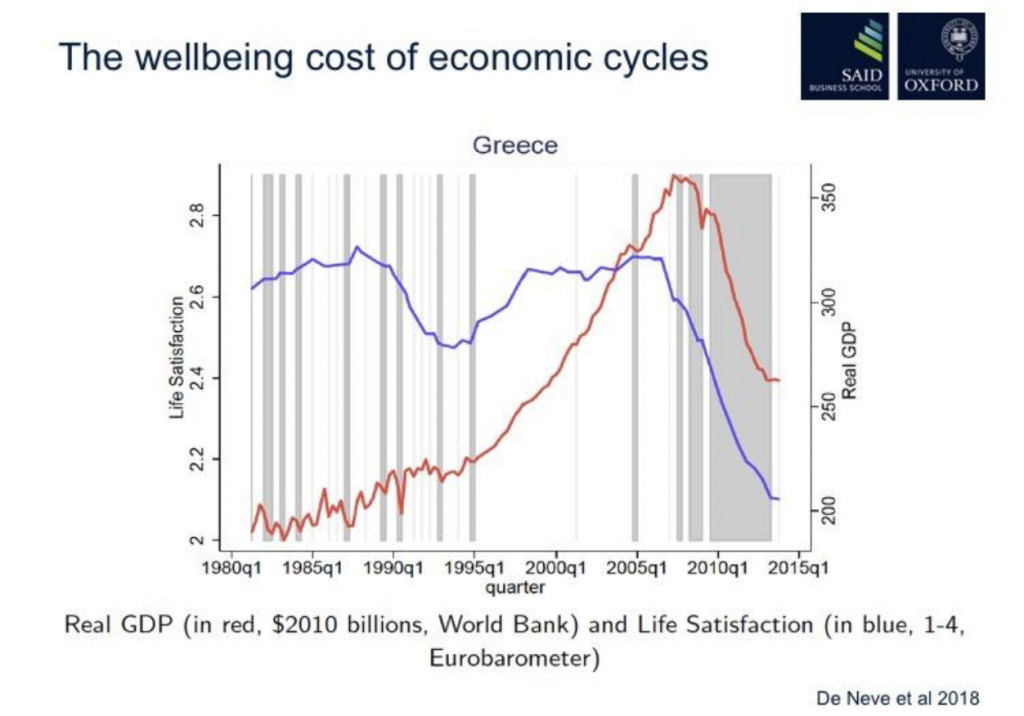

It turns out that people are more sensitive to losing security than gaining it. The following graph from Greece shows flat levels of wellbeing during substantial economic growth, then an epidemic of misery during the recession. A trawl of global datasets shows that people are twice as sensitive to a % point reduction in growth compared to a % point increase in growth.

Analysis of the impact of job insecurity on individuals finds a similar phenomenon. Even worse, an experience of redundancy or extreme job insecurity has a scarring effect: people who have experienced it are more likely to stay unhappier even if they find a new job.

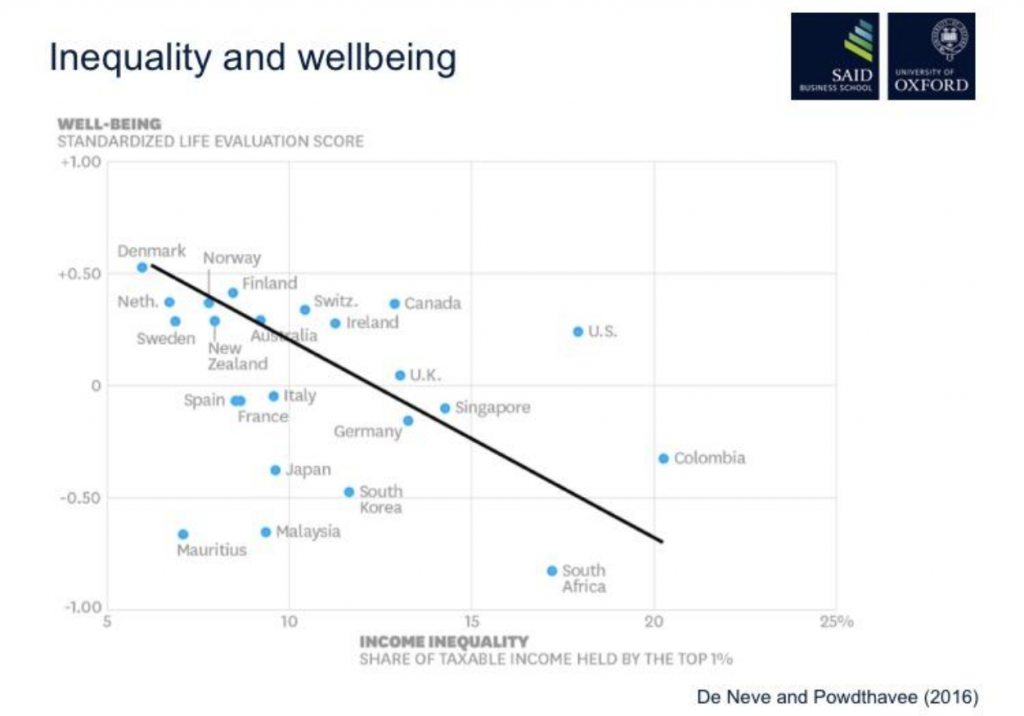

Another driver of misery is inequality, represented in the following graph. A feeling of unfairness makes us miserable. De Neve explained how exposure to unfairness in laboratory tests not only makes people feel miserable but it reduces their motivation to do any work. So inequality not only drives misery, but reduces productivity. There is a very high price to pay for inequality.

All this spells big trouble ahead in Wales. With the prospect of a recession growing rapidly, we are heading for a period of more misery. Right-wing populism will flourish in this environment, giving the means to unhappy people to wreak vengeance on a humiliating and unfair system.

If there were no alternative in sight, then we would all be looking into the abyss of further disintegration and spiralling misery. But there is an alternative. It has been growing for decades. Enter, “wellbeing economics”. In the next post, I chart the rise of “wellbeing economy” idea and its emergence as a much more useful measure than the traditional obsession with growth/GDP.

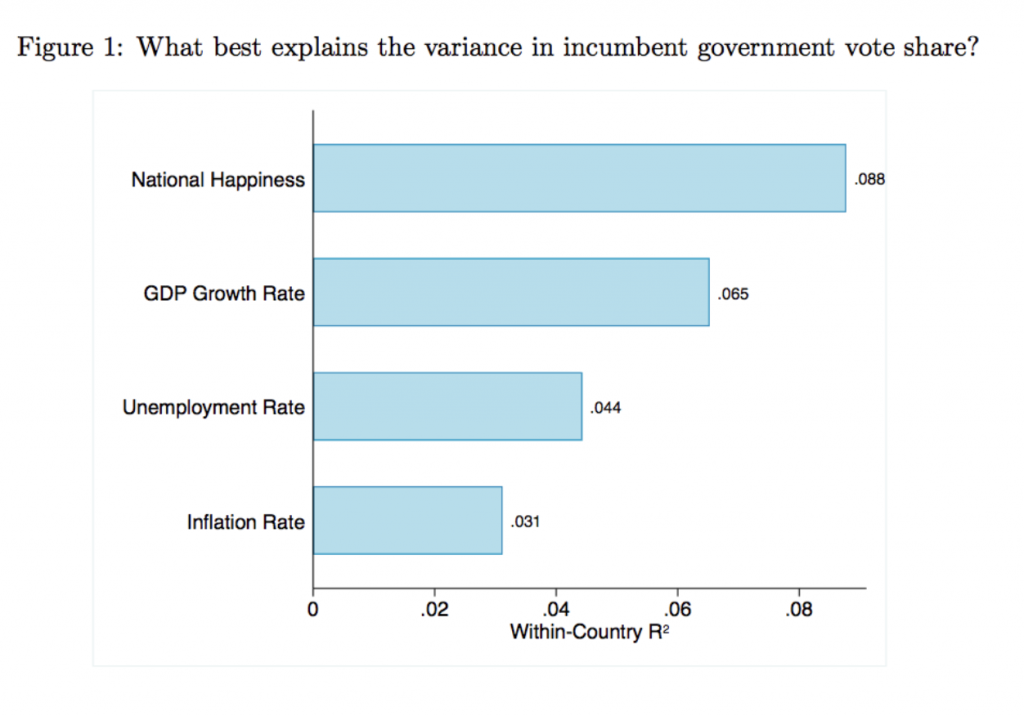

The wellbeing data pack a punch for politicians. George Ward has just published data to show that the answer to the question “How satisfied are you with the life you lead?” is a better predictor of election results than GDP, unemployment rate or inflation rate. He looked at data across the European Union since 1973.

He computed that a 1 standard deviation change in the wellbeing measure predicts a 6.1% vote swing. People who are happier are more likely to vote for the existing Government, irrespective of whom they voted for in the previous election and what their ideological position is relative to the current Government.

He computed that a 1 standard deviation change in the wellbeing measure predicts a 6.1% vote swing. People who are happier are more likely to vote for the existing Government, irrespective of whom they voted for in the previous election and what their ideological position is relative to the current Government.

The researcher concludes rather modestly, “It may well be in a Government’s own electoral interest to collect and use subjective wellbeing data in policy making.”

In the next post, I look at the emergence of wellbeing metrics and the growing challenge to GDP as an adequate measure.

For further discussion, Duncan Fisher can be contacted on [email protected]

All articles published on Click on Wales are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.