Dylan Moore reviews I, Eric Ngalle, a migration memoir published by Parthian Books

On page 81 of Eric Ngalle Charles’ memoir, the author – by now a well-known poet, performer, workshop tutor and all-round cross-continental Cymric Cameroonian bon viveur – relates a memory of a day he spent ‘skiving off school’. In place of formal instruction, his eldest sister teaches him English idioms, including ‘the devil makes work for idle hands’. Instead of listening, the young Eric Ngalle freely admits to being bored and not paying attention, eventually deciding to take his brother’s bike for a ride, despite having never ridden one before. He ends up crashing into Mbamba Limunga, a formidable lady who slapped and kicked the young reprobate with ‘all the force she could muster’. Returned unceremoniously to his sister, Eric endures a ‘series of verbal abuses, tirades and rants’ which end in a peal of laughter: ‘You see I told you the devil makes work for idle hands.’

It is the ‘skiving off school’ that appeals to me, idiomatic phrasing much less well known globally than the reference to the Book of Proverbs, but more indicative of a journey that ends up in Ely, Cardiff. Subtitled One man’s journey crossing continents from Africa to Europe, Charles’ memoir charts a changing consciousness as much as a remarkable story. Even before the uprooting that forms the basis of the narrative, Eric Ngalle Charles – as his name suggests – had a postcolonial, multicultural identity.

Steeped in traditional religion and ancestor legends as well as a Roman Catholic upbringing, the writer brings singular perspective to a unique autobiography, reading symbolic power into scenes as simple as his daughter pointing at pictures in The Very Hungry Caterpillar. It is, to Charles, the completion of his metamorphosis: ‘from Cameroon via the mountains of Ahun in Sochi, Russia, to be her father on a council estate called Ely in a small corner of Wales.’

Before we reach the sanctuary of Cymru – ‘the country that gave me back my name, my voice, my identity’ – the narrative focus is the two years and two months the author spent in Russia. Six months shy of his eighteenth birthday, Charles arrived at Sheremetyevo airport in Moscow, trafficked out of Malta by those who had tricked him into thinking he was flying to Europe to take up a place at university in Bruges.

First it must be said that Eric Ngalle Charles is a remarkable man. That he is still alive to tell the tales related here – of human trafficking barons, petty bullies and thieves, con artists selling fake dollars to Russian gangsters, racist skinheads roaming the transport network looking for Africans to pulverise – is something of a miracle. Second, and hardly less importantly given that this is a book review not a character appraisal, Eric Ngalle Charles is a remarkable writer.

Adopting the natural style of a person verbally relating anecdotes, the narrative voice is very close to the reader, sometimes addressing ‘you’ directly. Sometimes this is reassuring, at others discomforting. There is an unflinching, matter-of-fact tone to the way a whole range of taboo subjects are related. Witchcraft, torture, gratuitous violence, drugs, three-way sexual encounters, matters of the heart. Love and lust are given equal attention. Swear words are used sparingly. The balance of euphemism and direct language is exquisitely handled. In Petchatniki, a run-down hostel where ninety per cent of the clientele are illegal immigrants one rung up from ruin, people ‘would drink themselves into an uncontrollable stupor’. Eyewitness and participant, Charles takes us to places even the best undercover journalists never could.

That for the most part he relays the story with a grisly kind of relish is testament to the author’s survivor instinct. Several times, and quite understandably so, the writer comes close to suicide. Indeed, a nit-picking reviewer would perhaps explore the fact that the phrase ‘For the first time in my life I contemplated suicide’ appears many pages after previous ‘suicidal thoughts’. In fact, on only the third page Charles writes: ‘if death embraced me in Russia, I would have accepted it without grumbling’. But this is not a book for picking nits out of. As Charles writes in a couple of paragraphs squeezed into the limbo-land between the end of the narrative and an Afterword: ‘it has taken me the best part of nineteen years to be able to write down this very dark memory’.

Like any memories filtered through the bifocals of time and trauma, there is a rambling quality to some of the reminiscences, some focus on incidental details at the expense of the big picture, but if you read the book you’ll understand why Charles will not have been taking notes at the time. What is undeniable is the raw power of memory to disrupt even the most settled present.

The success of the book is also built on the way the narrative oscillates between events in Russia in the late nineties – a strange kind of coming-of-age tale during the years in which by rights the author should have been at university – and his childhood in the village of Small Soppo, near the foot of Mount Fako in south-west Cameroon. Repeatedly the writer makes clear that his quick acquisition of the Russian language saved his life on many occasions, as well as contributing to situations in which he was unwillingly cast in the lead role when dealing with dangerous individuals in the criminal underworld.

Charles’ childhood memories are related in italics and with a wistful tone. They range from nostalgic and bucolic – digging for Cocoyams – to the scandal of trying to kiss Enjema behind the Apostolic Church, and terrifying encounters with the juju man and a rhinoceros viper. But the tragedy of his early years is contained within the rejection Charles received from his father’s family. ‘Do you know Eric, the boy sitting next to you?’ his relatives are asked, one by one. Each denies him. ‘It was as if,’ writes Charles, ‘the devil had placed his hands inside my throat and into my stomach.’

If this was a turning point that sent Eric Ngalle Charles tumbling, mishap after mishap toward the hell of Petchatniki, his arrival in Wales has seen the devil have his work cut out. Since he first laid eyes on the National Express Bus to Swansea via Cardiff at Heathrow Airport, Eric’s hands have been far from idle. If there is something touchingly familiar about the bus driver, ‘belly resting comfortably on the steering wheel… eating what I later discovered to be KFC’, it is all the more so for its picture of home-going coming after the hellish experiences that come before, and for the fact that the writer of these words did not know yet that Wales was home.

All articles published on Click on Wales are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.

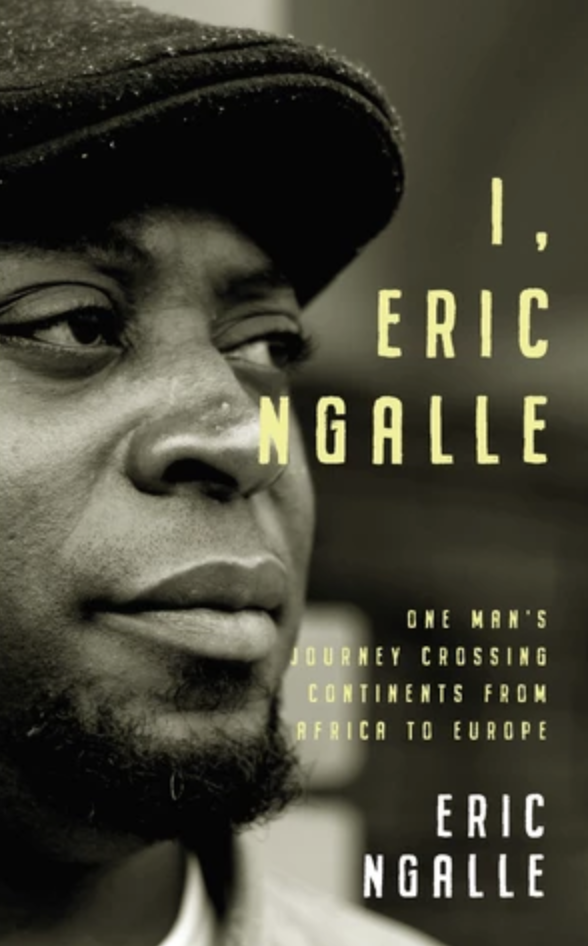

Picture provided by Parthian Books.