Joe Atkinson reviews Dr Wyn Thomas’ biography of a largely forgotten figure

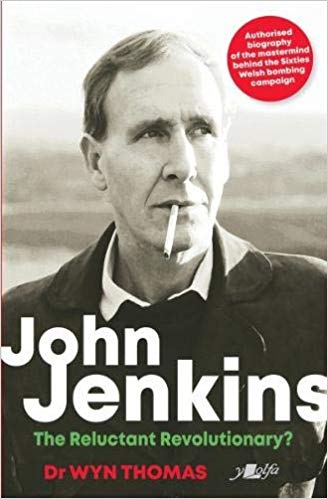

John Jenkins: The Reluctant Revolutionary?

Wyn Thomas

Y Lolfa, 2019

Take a stroll down your average Welsh high street canvassing public opinion of John Barnard Jenkins and responses might range widely based on the politics of the individuals surveyed. A principled freedom fighter and Welsh national hero? Or a fanatical terrorist and enemy of the British state? Militant activists in the mould of Jenkins invariably illicit contrasting, partisan and hyperbolic reactions.

However, in all likelihood the vast majority of your sample would simply ask who? For while he is undoubtedly one of the most influential figures in the Welsh nationalist movement, Jenkins has shunned publicity for half a century since his arrest for plotting the bombing of Charles Windsor’s investiture as Prince of Wales.

In his new book, the historian Dr Wyn Thomas sheds new light on the life and motivations of John Jenkins, going far beyond the hyperbole to get to the truth of a man he hypothesises was a ‘reluctant revolutionary’. Thomas’ 2013 debut monograph, Hands Off Wales, chronicled the Welsh nationalist movement in the 1960s, which culminated in the bombing of the investiture by Mudiad Amddiffyn Cymru (MAC), the ‘Movement for the Defence of Wales’. In John Jenkins: The Reluctant Revolutionary? he digs deeper, presenting a meticulously compiled examination of Jenkins, the man who spearheaded the campaign as MAC’s director of operations.

This authorised biography is set against more than a decade of interviews with Jenkins himself, as well as with his family, friends, associates, and those who don’t regard him so warmly. The book is truly impressive in its scope and search for truth above all else.

Truth, and its manipulation by the ruling classes, is a theme that runs through the spine of this biography. Jenkins is fixated on the idea that authorities subjugate populations by misrepresenting history and peddling their ‘truths’. Through Thomas, a now 86-year-old Jenkins lays out his own truth in minute detail, speaking candidly on not only how he did what he did, but why.

Perhaps inevitably, the book’s headline-grabbing revelation is that MAC could have assassinated Charles Windsor at his Caernarfon investiture, the fiftieth anniversary of which passed in July. Jenkins insists that the group he led comprised individuals willing to die for the Welsh nationalist cause. He even divulges that he could have been the one to fire the bullet to end the young prince’s life and change the course of history.

This disclosure is quite inconsistent with Jenkins’ personality – he’s not a man to dwell on what might have been and throughout the book seeks to avoid hypotheticals. The fact of the matter is that while MAC could have killed Charles, they did not. Nor did they pull a trigger for the cause. Jenkins talks of his commitment to a ‘hearts and minds’ campaign to win over the Welsh public while leader of MAC and insists that the group never set out to kill or injure anyone.

But the campaign was not without bloodshed. Two MAC members died transporting a bomb intended to detonate at the investiture, while a 10-year-old boy’s life was forever changed when he kicked a device that had failed to explode on the day. How heavy these facts weigh on Jenkins’ conscience is unclear; he expresses remorse for the victims but remains convinced MAC’s actions were entirely justified and in pursuit of a righteous cause.

Jenkins tells Thomas that he was inspired to the cause of Welsh nationalism and militant activism by the failure to protect Wales by political means. He speaks of the profound impact of the Aberfan disaster and the flooding of the Clywedog and Tryweryn valleys on his psyche and that of the whole nation. Targeting the pipes that carried Welsh water to English cities was a symbolic retaliation by a nationalist movement that found its voice in the 1960s, a decade of global revolution, rebellion and non-conformism.

Thomas does well to set Jenkins’ story against this historical context. The book’s structure is simple, a linear exploration of Jenkins’ life from birth to the modern day, a 400-page personal, distinctly Welsh odyssey through eighty years of global revolution.

Delving deeper into the book, you realise that Jenkins lived a rich life outside of the movement that defined him. As a younger man in his mid-twenties, he got the opportunity to see the world with the British Army. Stints posted in Berlin and Cyprus not only provided a colourful departure from family life in the declining industrial south Wales valleys, but also give context to his transformation from moderate patriot to violent militant.

Jenkins’ insights into the nationalist Cypriot movement EOKA are particularly fascinating; he discusses seeing first-hand how a small but organised group of revolutionaries can free a country in the grips of colonialism. These experiences heavily influenced the way Jenkins would go on to lead MAC – a small, tight-knit group of activists that had a profound impact on the road to devolution in Wales.

Syniadau uchelgeisiol, awdurdodol a mentrus.

Ymunwch â ni i gyfrannu at wneud Cymru gwell.

Through his interviews, Thomas allows his subject’s personality to shine through the pages. He does not impose his own personal feelings about a man with whom he developed a close enough relationship for the private and distrusting Jenkins to open up. Jenkins comes across as intelligent and principled, but also single-minded and often arrogant, insisting that he cannot engage in a task without being totally committed. Thomas explores the impact this single-mindedness has had on his life, in the breakdown of personal relationships and the struggle to build new ones.

He is also deeply idealistic, professing that his one true love got away at the tender age of fifteen. The way he dwells on this relationship – which he admits he has idealised – reveals a contradiction in the personality of a man who is otherwise unwavering and unapologetic about the actions he has taken.

This is a sympathetic deep-dive into the mind and motivations of a principled and emotionally rigid man who delivered some of the biggest blows in the name of Welsh nationalism. The reluctance with which Thomas characterises Jenkins is certainly true of his diffidence towards self-promotion, but the complete conviction with which he pursued his brand of militant nationalism shows he was certainly not reluctant to act. Thomas ultimately allows the reader to make their own judgement about John Jenkins, a much more complicated man than many would expect.

All articles published on Click on Wales are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.