John Cordner examines the impact of the pandemic on Wales’ position in the Union.

The Covid-19 pandemic had, and is still having, a sweeping impact across the UK; it raised questions about the sustainability of supply chains, the government’s ability to rule the country and the state’s role in Britons’ lives.

What was constitutionally unique about the pandemic is that never before had the management of a national crisis been so diffused between the four nations; Wales was able to set its own policy over testing, lockdowns, mask mandates and restrictions. During the pandemic, the Senedd flexed its constitutional muscles to push against Westminster’s pandemic response, culminating with a temporary hard border with England.

Over the last decade, Holyrood has demonstrated how conducting politics and policy in opposition to Westminster can fuel desires to weaken a centralised, London-based government. This begs the question: has Mark Drakeford’s Covid-19 policy had a similar impact in Wales? As the Independent Commission on the Constitutional Future for Wales consultation continues we must seize the opportunity to consider the impact of the pandemic, which will likely influence its findings.

Health services are almost entirely devolved; the Senedd is responsible for running the NHS in Wales. This meant that when the pandemic hit, Wales could set its own policy and the measures introduced by Welsh Labour and the Senedd were far more restrictive than those introduced in England by the Conservatives. Drakeford and Welsh Labour followed a scientific, evidence-based approach that involved making decisions based on the most recent data available. This policy doctrine resulted in a pragmatic attitude towards removing Covid-19 restrictions, applying them longer and more stringently than in England. These restrictions undoubtedly helped limit the spread of Covid-19 within Wales. This was in strong contrast to the approach taken in England by then Prime Minister Boris Johnson and the UK Government, which, as the pandemic drew on, moved away from an evidence-based approach and towards seemly random restrictions such as a tier-based system with no logical consistency.

The Johnson government passed laws to focus the spotlight on niche parts of restrictions to avoid scrutiny on its poor handling of Covid, such as during the 2021 Omicron tier based restrictions using the term ‘substantial meal’ to define whether or not alcohol could be served in pubs. This created an England-wide debate on what was and was not a substantial meal, with different government ministers giving different definitions and avoiding scrutiny on the overreliance on vaccines to deal with the Omicron variant despite prior knowledge the vaccine became less effective, and the increasing revelations about parties in Downing Street during lockdown. The lack of a science based policy culminated in fixed dates for the removal of restrictions regardless of the Covid-19 situation with ‘Freedom Day’ being called ‘both unethical and illogical’. England suffered ‘egregiously poor outcomes’ during the pandemic, with one of the worst death rates per capita from Covid in the world.

By appealing to the social-democrat instincts of the majority of Welsh voters, Drakeford increased the calls for greater devolution in Wales.

The reason this comparison is so meaningful is that it highlights to Welsh citizens and Welsh voters that if health was not a devolved power and the pandemic in Wales had been managed by Johnson and the UK government as opposed to Drakeford and Senedd Cymru, it is pretty safe to conclude there would have been many more deaths in Wales. Welsh people are aware of this; polling done by YouGov in the middle of the pandemic shows that 60% of Welsh voters prefer the approach taken in Wales towards the pandemic, with 17% preferring the approach taken in England.

The logical answer to the question posed in the title is that, yes, both calls for devolution and independence in Wales may have increased over the pandemic because of the perceived success of the Senedd’s Covid-19 response. However, the answer is more nuanced because of the role played by Drakeford, the mastermind of the Welsh policy that proved so popular. Drakeford’s ability to frame the pandemic in a way that aligns a socially democratic Wales against neo-liberal England is the sort of political positioning that would have the sultans of spin Mandelson and Campbell salivating. Drakeford’s handling of a once in a generation political crisis encouraged trust in his steady decision-making and thoughtful policy proposals in a time of massive uncertainty that came after two long years of deep uncertainty and turmoil over Brexit. Drakeford clearly desires greater devolution, but not complete independence, and this is likely to be the legacy of the pandemic in Wales on the Union.

Mark Drakeford is probably the politician whose reputation has been enhanced most by the pandemic in the whole of the UK, transitioning from being perceived as an academic politician to becoming an incredibly popular national figure. When Welsh voters’ main concerns were to do with pandemic related issues, with health listed as ‘the most important issue facing Wales’ for the vast majority of the pandemic, Drakeford’s steady leadership was seen as reassuring and appropriately cautious in a time of uncertainty,the perfect tonic for chaos on the national level. Welsh voters were alert to the stark contrast between Drakeford’s Welsh Labour and Johnson’s Conservative party, with Drakeford presenting the personality differences between them as a sign Johnson was not taking the pandemic seriously while he was. Trust in Drakeford on Covid 19 management was sitting at 55% by September 2021, while trust in Johnson was at 28%, with 65% saying they had ’no trust at all’.

Robust debate and agenda-setting research.

Support Wales’ leading independent think tank.

Adamson argues that Welsh identity is, at its core, a fusion of soft nationalism and social democracy. Using this rationale, Adamson claims that Welsh Labour’s ability to represent this identity through state-backed socialist economics with a Welsh dimension has allowed the party to thrive and dominate the Welsh political sphere for 100 years. Drakeford channelled this identity through his rhetoric during the pandemic, consistently emphasising the role social democracy would play in moving Wales away from the pandemic. Drakeford positions the Union as fractured by a divide between a socially democratic Welsh people and a neo-liberal Conservative Westminster. While both have a place in a multinational Union, territorial and ideological diversity mean that powers should be devolved to allow Welsh Labour to act on the desires of their social-democrat electorate.

Drakeford and Welsh Labour were publicly critical of Johnson and the UK Government’s levelling up policy, arguing that a Senedd-organised policy programme could deliver radical ideas to deal with the fallout of leaving the EU, the pandemic and the ‘UK Government’s determination to erode the Senedd’s powers’. Covid 19 policy followed by Welsh Labour, which is not conventionally seen as socially democratic or even on the left/right spectrum, was framed by Drakeford and the Welsh Government as fitting in with their understanding of social democracy. For example, circuit breaker lockdowns were very popular among Welsh voters, especially among Welsh Labour’s voter base. This was done to associate popular policies with their understanding of social democracy.

By appealing to the social-democrat instincts of the majority of Welsh voters, Drakeford increased the calls for greater devolution in Wales. By othering the UK Conservatives and specifically Johnson as neo-liberal, English and distinctively non-Welsh, Drakeford and Welsh Labour have helped foster a feeling of separateness under a socially democratic Welsh administration based in Cardiff. Drakeford and the pandemic have made the Welsh people aware of the full extent of the Senedd and the number of devolved powers it exercises; 40% of Welsh voters did not know healthcare was devolved before the pandemic. This newfound understanding of the level of devolved powers to the Senedd could increase the opportunity for Welsh voters to see the Senedd as their primary parliament and desire for social democracy to be achieved in Wales by the Senedd rather than Westminster.

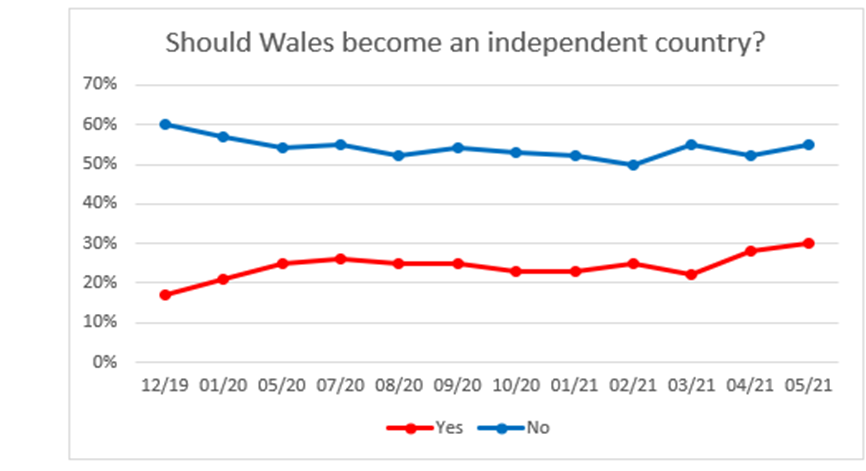

There is a logical chain to follow that if calls for greater devolution have increased, that independence as a more extreme form of devolution should also have increased. The polling data supports this analysis. Below is a graph showing polling on Welsh independence from the start of the pandemic up until the day before the 2021 Senedd Elections with gaps between certain months due to a lack of data.

Graph 1: Should Wales become an independent country? Data observable on this link

The ‘Yes’ trend increasing over time shows an increase in support for independence, which has led to a increase in the possibility and support of independence, but this does not mean independence will occur any time soon. It is safe to conclude that from a period of history where the number one issue on the Welsh Electorates mind was a governments handling of the pandemic that this is the result of Drakeford’s pandemic mangement. While data is not availble to corralate Drakeford’s approval ratings and increased support for independence, when the only issue on Welsh voters minds is pandemic management and support for independence increases dramatically, it is far from a coincidence. It is logical when imagining an independent Wales to imagine the First Minister as the Head of State, so when a leader has high approval ratings based on their governance, and when the approval of the then Prime Minister being so low, that Welsh people may be wished to be governed fully by their prefered leader, not just within further devolved structures. This can explain the increase in ‘Yes’ and decrease in ‘No’ observable on Graph 1, with the lead for ‘No’ falling from 43% at the start of 2019 to 25% by May 2021.

The legacy of the pandemic era in Wales will be one of new-found self belief in self-governance of the Welsh electorate

With a new Prime Minister in office, the contrast with Drakeford and Johnson which fueled support for Drakeford it could be argued may dampen the effect of the pandemic on support for Welsh devolution and independence. Truss was not involved with the Westminster’s pandemic policy and so logically would not be as attached to Johnson’s failure. However, despite this being true the damage is already done, independence polling has not rebounded to pre-pandemic levels, with ‘No’ leading around 20-30% where in the early 2010s a lead of 70% was not uncommon. Furthermore, Drakeford’s framing of the English Covid policy as neo-liberal has proven to be increadibly apt when you consider the hardline ideological positions of the Truss administration so far. The Welsh people have clearly made this association between Truss’s ideology and the poor Johnson pandemic management aswell as a general disdain for neo-liberalism in the Welsh political sphere. In a poll conducted by YouGov and The Sunday Times in August 2022 before Liz Truss became PM ‘No’ lead by 28%, when asked the same question but with the additional factor of Liz Truss becoming PM the fell to just 18%.

Drakeford does not push for independence, but this does not mean his high approval based on his pandemic mangement and his pushing for greater devolution does not impact the views of the electorate. While independence is not occurring anytime soon, the legacy of the pandemic era in Wales will be one of new-found self belief in self-governance of the Welsh electorate, which has lead to increased calls for devolution and independence in Wales.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.