Adam Somerset reflects on the legacy of Welsh MP Leo Abse, 50 years on from the publication of his memoir

Leo Abse published his memoir Private Member 50 years ago. Elected in a by-election in 1958 he served as Member for Pontypool until 1987. Mrs Thatcher vetoed his elevation to the House of Lords.

He held no ministerial office. Instead he introduced more private member’s bills than any other parliamentarian in the 20th century. Of his role in the Commons James Callaghan said: ‘You do more good in terms of human happiness than 90% of work done in parliament on political issues.’

As a young MP Abse had received advice from Aneurin Bevan to cultivate irreverence. Returning home to Jenny Lee in the evening Bevan reported Abse’s response: ‘however the English ruling classes might appear to a Celt, to a Phoenician they are mere parvenus.’

Abse was the first parliamentarian to initiate debates on genetic engineering, the dangers of nuclear power generation, in vitro pregnancy.

Leo Abse was a dandy whose dress preference made his distinguished tailors, Kilgour, French and Stanbury of Dover Street, nervous. A favourite outfit was a brown and black Prince of Wales check suit with cuffed sleeves, a lapelled waistcoat and no turn-ups. Abse’s appearance was completed with a huge amber signet ring. Of his tailors’ work Abse said: ‘since I’ve been elected one of the ten best dressed men in Britain, they’re getting into the spirit.’

Abse was the first parliamentarian to initiate debates on genetic engineering, the dangers of nuclear power generation, in vitro pregnancy. He was an authority on suicide, delinquency, adoption, the prison system, capital punishment, homosexuality, contraception, the legitimacy of children, widows’ damages, industrial injuries, disability, relief from forfeiture.

The memoir has three major virtues to recommend its reading fifty years on. One is its evocation of the culture of the House of Commons. He observes that prior life and reputation are of small account:

‘The insensitive or arrogant who dare to challenge these rules are soon humiliated: the millionaire, Captain Robert Maxwell, possessed of boundless animal energy and born too poor to afford deference, is soon humiliated by mockery; a John Davies, with the hubris of the unfeeling successful accountant, is speedily and mercilessly savaged.’

Even in 1973 Abse is observing ‘young people propelled into Parliament with insufficient experience.’ He notes that the Daily Telegraph recorded of his first speech ‘Mr Abse spoke with a force and clarity approaching of an experienced parliamentarian.’

But the shock of arrival is profound in personal impact. His is a rare voice to record it.

‘The outward calm was, however, a sham. The first year of my parliamentary involvement was one of the most painful periods in my life. The nights after I left the Commons for my lonely hotel room were full of nightmares and terror: seemingly for hours I would, in a twilight world, between dream and wakefulness, be gripped by vertigo. The whole room would spin around me, now slowly, now like some ghastly merry-go-round totally out of control.’

He observes the culture of the Members from Wales. In the summer of 1972 the mother of a Welsh Member died at a great age. The Chief Whip, Bob Mellish, had issued a three-line whip. He was astounded to find that the entire body of MPs from Wales had ignored it and gone to attend the funeral.

The second government of Harold Wilson was a time of reforming social legislation, more over a short period than in any decade since. Abse himself describes his resolve: ‘When I returned to the Commons in 1966 I was determined at the early stage of a new Parliament, when no electoral considerations could be pleaded by the knock-kneed, once and for all to dismantle our barbaric homosexual laws.’ Roy Jenkins at the Home Office assures him that he will insist in Cabinet that time be given to the Private Bill to pass.

Innovative. Informed. Independent.

Your support can help us make Wales better.

All politics are steeped in tumult. When it came to abortion reform Abse reports a cross-departmental breakdown. The clash between the Home Office and Department of Health that became ‘a matter of immediate comment in the House’. Abse finds praise for Norman St John Stevas: ‘he led the campaign for an enquiry with extraordinary stamina and courage, braving the derision and distortions…with dignity.’

The history of Labour is one of dispute. Abse’s adversaries include Tony Benn of whom he writes ‘his year of office as Party Chairman was disastrous.’ Rancorous letters are sent that run to three pages. He ends with the comment ‘Undoubtedly, some of his best friends are Jews.’

He is impatient with ministers. ‘Stafford Cripps was only one of many statesmen who could out-argue the whole Cabinet, and be absurdly wrong.’ Of the Minister in the Home Office he recalls ‘my encounter with Alice Bacon’s ministerial incapacity was one of too many that I have been compelled to endure.’

There is a tradition in Westminster of the strong independent back-bencher, a tradition that the Senedd in its youth has not yet engendered.

It took until 2017 for Alice Bacon to be the subject of a biography. The author was Rachel Reeves, the book written during her time of absence from the shadow front bench. A wise judgement runs: ‘Although Britain needed charismatic and determined back-benchers like David Steel and Leo Abse to almost obsessively drive forward the change that happened on abortion and homosexuality, it also required practical politicians like Alice Bacon to help steer reform.’

A demerit to Private Member is the author’s deep immersion in psychoanalytic theory. John Campbell, the biographer of Roy Jenkins, referred to him as ‘a mischievous amateur Freudian’. Rachel Reeves in 2017 took a similar view. This aspect, which does not detract from the political accomplishment, occurs on occasion in passages like:

‘Living out his own romance, the conventional politician does not wish to acknowledge the widening gulf between himself and his constituents. For it must not be overlooked that the politician casts himself as as his own hero; too often he has not stepped out of the romantic role that, as a child, he wove to restore for him the bliss he enjoyed before a critical estimate of his parents’ actual place in the social world…For all of us, as for him, once upon a time our parents were Olympians and we shared their special privileges…’

James Callaghan is viewed through the lens of his childhood: ‘certainly not exempt from the syndrome associated with the fatherless child…lacking the boundaries imposed upon a boy who has to model himself on a real living blemished father.’

But the Freudianism is all part of a powerful, purposeful persona. There is a tradition in Westminster of the strong independent back-bencher, a tradition that the Senedd in its youth has not yet engendered. Above all ‘Private Member’ is a reminder of an era, that for all its surface turbulence, contained greatness within it.

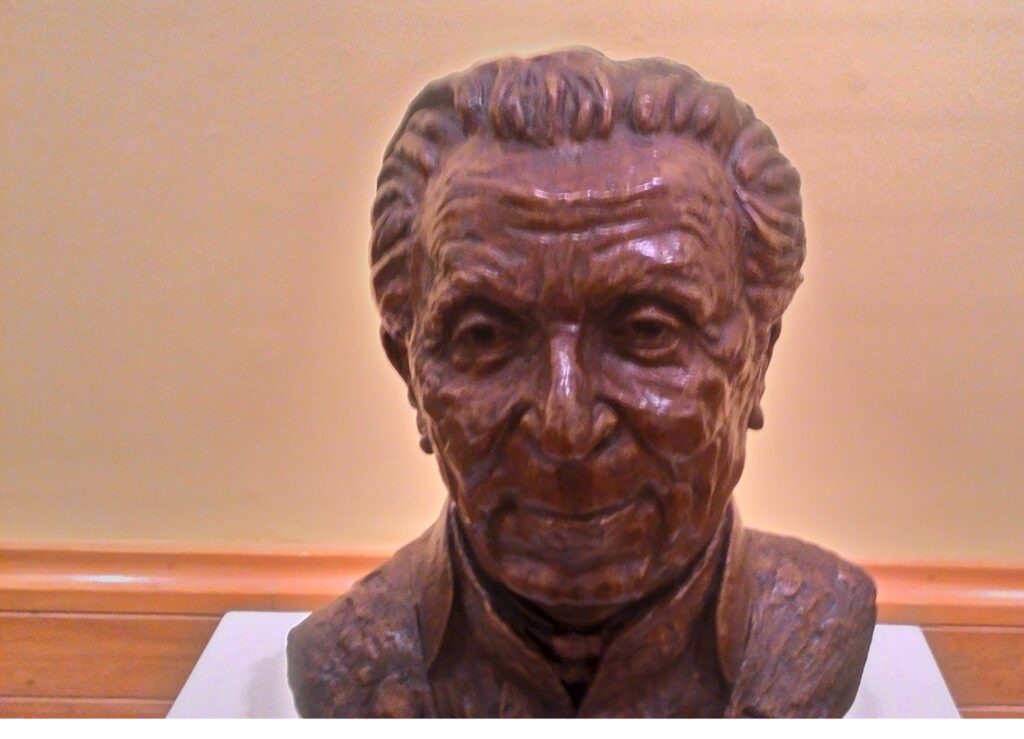

A bust of Abse is held by the National Museum of Wales. The sculptor was Luke Shepherd, a second cousin of Abse. Unveiled in 2009 it is in storage and not on public display.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer. If you want to support our work tackling Wales’ key challenges, consider becoming a member.