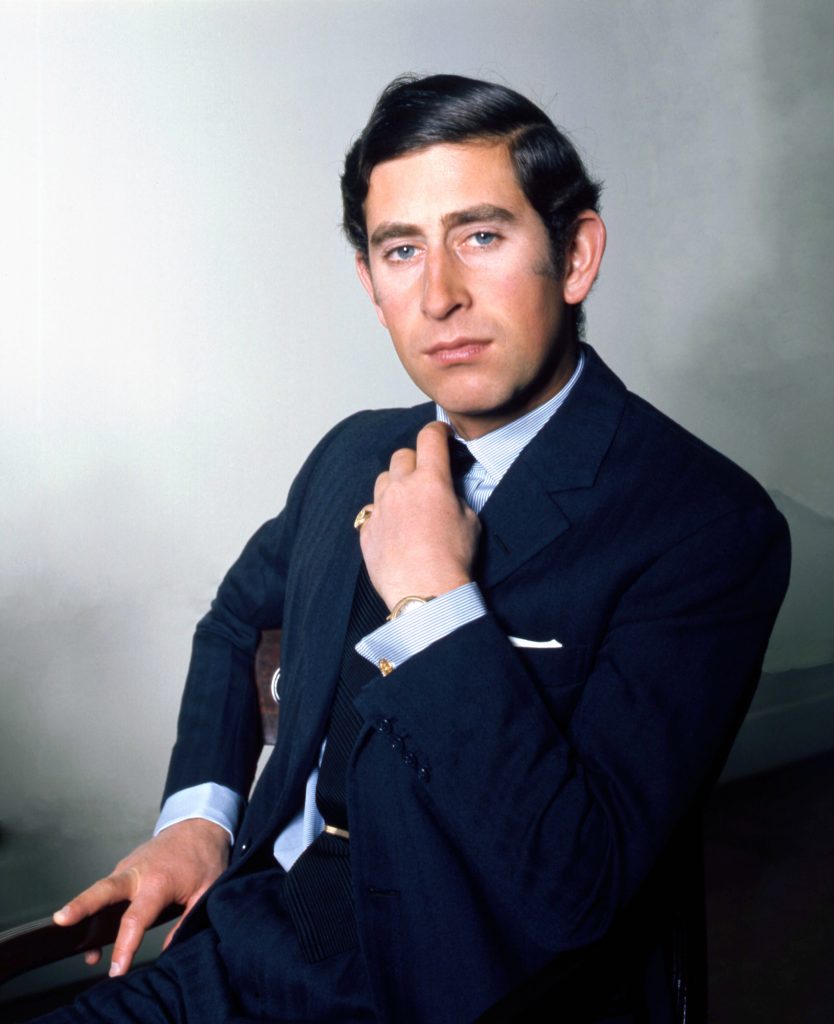

Ahead of the fiftieth anniversary of the Investiture of Prince Charles in July 1969, Robert Jobson looks at the relationship between a Prince and a country.

This article was originally published in the welsh agenda: issue 62

When Peter Beck, headmaster of the preparatory school Cheam, summoned a group of boys to his sitting room on 26 July 1958, pupil Prince Charles was amongst them. The Commonwealth Games in Cardiff was being broadcast on the BBC and the boys were invited to watch the closing ceremony on Beck’s television set. It was announced that, while the Queen was unable to attend, Her Majesty would instead address both the packed stadium and the television audience in a recorded message.

The prince’s mother then appeared on the screen and read out a simple, but, for Charles, life-changing message:

‘The British Empire and Commonwealth Games in the capital… have made this a memorable year for the principality. I have therefore decided to mark it further by an act that will, I hope, give much pleasure to all Welshmen as it does to me. I intend to create my son Charles Prince of Wales today. When he is grown up, I will present him to you at Caernarfon.’ His friends turned to the embarrassed young prince and offered their congratulations on his elevation in status, much to his discomfort. It was the first he had heard of it.

He later recalled the announcement at a Caerphilly Castle dinner in July 2008 to celebrate his half-century as the Prince of Wales:

‘I remember with horror and embarrassment how I was summoned with all the other boys at my school to the headmaster’s sitting room, where we all had to sit on the floor and watch television. To my total embarrassment I heard my mama’s voice – she wasn’t very well at the time and could not go. My father went instead and a recording of the message was played in the stadium saying that I was to be made the Prince of Wales. All the other boys turned around and looked at me and I remember thinking, “What on earth have I been let in for?” That is my overriding memory.’

The prince said later it was one of the greatest privileges possible to be the twenty-first Prince of Wales. ‘I have tried my best… to live up to the motto of my predecessors, Ich Dien – I Serve,’ he said. Eleven years later at Caernarfon Castle, the Prince’s investiture was modelled on that for his great-uncle David (later Edward VIII and after his abdication Duke of Windsor) in 1911. On the eve of the initiation Prince Charles boarded the royal train with his parents bound for north Wales. They knew that the pageant had to be perfect and hoped for a positive response. They had no choice but to trust in the security already in place. Nationalist fanatics had formed what they called the ‘Free Wales Army’ and had finally won the attention of the police and security services who were now taking the threat seriously after an RAF warrant officer was seriously injured in an incident. Then the gang planted a bomb at Temple of Peace in Cardiff. Another was found in the lost-luggage department of the railway station. Anonymously, too, it was announced that the Prince of Wales was on their target list. Charles was understandably a little uneasy.

After four terms at Trinity College, Cambridge, the prince was sent to the University College of Wales at Aberystwyth in order to learn Welsh before his formal investiture as the Prince of Wales. This was a political decision rather than a cultural one, amid a revival of nationalism in Scotland and Wales. Just before his departure to the Welsh college, Charles recorded his first radio interview and, not surprisingly, he was asked about his attitude towards the hostility in the principality. ‘It would be unnatural, I think, if one didn’t feel any apprehension about it. One always wonders what’s going to happen… As long as I don’t get covered in too much egg and tomato, I’ll be alright. But I don’t blame people demonstrating like that. They’ve never seen me before. They don’t know what I’m like. I’ve hardly been to Wales, and you can’t really expect people to be overzealous about the fact of having a so-called English prince to come amongst them,’ he said.

To cancel the university term in Wales would have been a public-relations disaster for the government and indeed for Charles himself. It was decided it would be a weakness to bow to extremist threats. So they went ahead regardless. Upon his arrival at Pantycelyn Hall, where he would share accommodation with 250 other students, Charles was met by a 500-strong cheering crowd. He was deeply touched. In the end the prince enjoyed his time there and was treated kindly in Aberystwyth. His period of study there passed without incident.

He wrote to a friend: ‘If I have learned anything during the last eight weeks, it’s been about Wales… they feel so strongly about Wales as a nation, and it means something to them, and they are depressed by what might happen to it if they don’t try and preserve the language and the culture, which is unique and special to Wales, and if something is unique and special, I see it as well worth preserving.’

Years later he said the time he spent studying there were among his fondest memories of times he has spent in Wales. He recalled with pleasure the ‘memorable times spent exploring mid Wales during my term at Aberystwyth University and learning something about the principality and its ancient language, folklore, myths and history.’

More bombs were threatened, promised by Welsh militants for Caernarfon on the actual day of his installment as the Prince of Wales on 1 July 1969. And despite the deaths of Alwyn Jones, 22, and George Taylor, 37, dubbed the ‘Abergele Martyrs’ after they died handling a bomb on the eve of the investiture, the event itself passed off without incident. Charles was driven through the town in an open carriage on his way to the castle past cheering crowds. As the guests and choir sang ‘God Bless the Prince of Wales’, he was conducted to the dais and knelt before his mother on a set designed by the Queen’s brother-in-law Lord Snowdon. He would later write that he found it profoundly moving when he placed his hands between his mother’s and spoke the oath of allegiance.

The Queen then presented the prince to the crowd at Eagle Gate and at the lower ward to the sound of magnificent fanfares. After that he was again paraded through the streets before retiring aboard the Royal Yacht at Holyhead for a well-deserved dinner, an emotionally exhausted but very happy prince. Buoyed by the experience, the prince noted, ‘As long as I do not take myself too seriously I should not be too badly off.’

The next day Charles set off without the rest of the family to undertake a week of solo engagements around the country. He recalled being ‘utterly amazed’ by the positive reaction he received. As the tour progressed south, the crowds grew even bigger. At the end of it, Charles arrived exhausted but elated at Windsor Castle. He retired to write up his diary, noting the silence after the day’s cheers and applause, reflecting that he had much to live up to and expressing the hope that he could provide constructive help for Wales.

There is no doubt that the Windsors used Charles’s investiture as a propaganda tool, a way of introducing their new hope to the world with pomp and pageantry. It was designed to bolster popularity for the monarchy’s image in Wales at the time the dynasty was suffering from an identity crisis and needed a PR boost. Years later in 2009, one of the driving forces of the spectacular event, Lord Snowdon, in an interview on the BBC, alluding to some of the more arcane aspects of the Caernarfon Castle ceremony said it was ‘all as bogus as hell.’ And as for the uniform Lord Snowdon had to wear in his role as Constable of Caernarfon Castle, he says that he designed it himself and reckons it made him look like a ‘cinema usherette from the 1950s or the panto character Buttons.’

It is unclear whether on ascension to the throne, King Charles will authorise another expensive investiture ceremony for his son and heir Prince William, Duke of Cambridge. But what is apparent is that since his investiture this Prince of Wales has developed a deep affinity with the people of the country.

Unlike previous bearers of the title, Charles has chosen to cultivate close contacts in Wales. He is by no means obliged to do so, and indeed none of his immediate predecessors did nearly as much. He purchased a 192-acre estate near the village of Myddfai, Llandovery, Carmarthenshire, through his Duchy of Cornwall trust, called Llwynywermod, also known as Llwynywormwood, just outside the Brecon Beacons National Park. Adapted from a former model farm in Carmarthenshire, it bears witness to his philosophy of sustainable building with a structure traditionally made from existing and locally sourced materials, an ecologically sound heating system and elegant interiors that harmonise perfectly with the architecture.

He uses it for meetings, receptions and concerts, and as the base for his several yearly visits to Wales, including the annual week of summer engagements, known in his annual schedule as ‘Wales Week’. He says he wants it to be a ‘showcase for traditional Welsh craftsmanship, textiles and woodwork, so as to draw attention to the high-quality small enterprises, woollen mills, quilt-makers, joiners, stonemasons and metalworkers situated in rural parts of Wales’. It enables him, he says, to feel part of the local community. To him, he says, preserving this sense of community ‘is timeless’.

When asked how important it was for him to have a retreat in Wales, Charles said: ‘Very important! Having been as Prince of Wales for fifty-five years [at the time of the interview], it enables me, on various occasions, to be part of the local community around Llandovery and to have a base for entertaining and meeting people from throughout the principality.’

He went on, ‘Wales has still preserved its wonderful sense of community, particularly in the rural areas, and Llandovery, an old sheep drovers’ town, somehow maintains those priceless assets of its own community hospital, family GPs, a rugby club [of which I am proud to be patron], a railway station and a strong connection with the family farming communities in the surrounding countryside. Some may say this is old-fashioned, but to me it is timeless; the bedrock of our humanity in a profound relationship with nature and the very heart of Wales’s cultural, social and spiritual heritage.’

All articles published on Click on Wales are subject to IWA’s disclaimer