Dylan Moore reviews a collection of poems looking at language and identity by Mike Jenkins, Eric Ngalle Charles, Ifor ap Glyn.

First, a disclaimer. I am a friend of Eric Ngalle Charles. But then, I ask you, on the Welsh literary scene today, who is not a friend of Wales’ most famous Cameroonian?

Eric’s recent crowdfunder – to help the poet, playwright and memoirist mitigate the effects of the many cancellations to his growing schedule of performances and events – attests magnificently to the affection and esteem in which he is held by his writing peers and a wider community of which he has made himself an integral part.

Much of this is down to the poet’s self-appointed role of ‘bridge builder’ between the two unlikely poles of his own life: Cameroon and Wales. As the wide-ranging introduction to this collection, by the Cameroonian poet and critic Joyce Ash, puts it: one of these nations is where Charles’ ‘umbilical cord is buried’; the other ‘gave him back his name’.

To complicate further the hybridity of the poet’s (largely positive) identity crisis, this slim volume is the result of the writer’s ambassadorial trip to his homeland in the company of Ifor ap Glyn, National Poet of Wales, and the veteran ‘Red Poet’ Mike Jenkins, unofficial Bard of Merthyr Tydfil.

These are two writers whose own cultural bridge buildings are expressed in works spanning the rivers that run between English and Cymraeg. Ap Glyn’s bilingualism and Jenkins’ Wenglish are together the perfect foil for Charles’ English, Bakweri, Pidgin English and Camfranglais, underlining what no doubt all three poets would regard as Wales’ (as well as Cameroon’s) postcolonial condition.

Interviewing Eric at this years’ Hay Digital, festival director Peter Florence responded to Charles’ self-deprecating remark, a claim to speak ‘broken English’ by summarising pithily and perfectly that Ngalle’s English is ‘broken in the most beautiful way’.

“Ngalle’s poems mix myth and memory, political and postcolonial commentary – and autobiography.”

This book is a monument to that observation. Eric’s arduous life story inadvertently birthed a voice so unique it spans continents in a couple of lines: ‘You see when I first took refuge in my friend’s house in Ely, / I wanted to tell him what had become of the cesspool of Crime / which became Pechatniki, Moscow’. Or: ‘I will chant in Sufi mystics, / as slowly, we disappear behind the hills of Treorci’.

Those who know and love Eric will know his geniality, his huge heart and his big belly laughs, and his poetry reflects his personality. It is full of the pleasures of the flesh.

‘My Favourite Foods’ begins by listing ‘Kwacoco’, ‘Banga soup’, ‘Ekwang’ and ‘Achu soup’; clearly the taste buds hold memories, comfort for the exile. But there are tears too, and trauma, and tragedy.

Charles’ employment of harsh imagery creeps up, understated. There are graves, blindness, mythical beasts and guillotines among the hibiscus flowers and palm wine, whose libations lubricate the poetry as well as the friendship between the poets.

Ngalle’s poems mix myth and memory, political and postcolonial commentary – and autobiography. In ‘Wana Wa Nyuwe – The Orphaned Children’ this potent brew comes together in the image of ‘my many fathers’, the successive European powers that colonised, brutalised and carved up Cameroon: ‘the Portuguese, then the Germans, then the English’ and that ‘crocodile with ghastly teeth’, the French, whose language dominates the country today and who, in Charles’ poem ‘came everlastingly’, a hint perhaps toward the country’s current travails.

Armed conflict persists in the Anglophone region where Charles is from, and Paul Biya has been President of the Republic since 1982, the longest-ruling non-royal leader in the world.

Elsewhere Ngalle knowingly mangles Cymraeg – ‘Dowin hoffi triog sharag cymraeg’ – in a kind of Pidgin Welsh that underlines the enthusiastic first forays into language of the newcomer, as well as the poet’s enthusiasm and ability to help building bridges within as well as beyond Wales.

Charles’ Pidgin Welsh is more than many a ‘native’ can manage, and is met in this collection by a similar sprinkling of words and phrases in the poetry of Mike Jenkins, who begins his trip with ‘Baggage’, where he reflects on his preference for the word ‘blodeugerdd’ (literally: song of flowers) which he introduces as ‘a word for the ju-ju man’.

In ‘Stopped by the Military’, Jenkins juxtaposes the serious state of contemporary Cameroon – a checkpoint that ‘felt like a flashback to 70s Belfast’ – with the humorous report that in the absence of his passport and needing ‘Something with your photo on’, he ‘fumbled for my Merthyr bus pass, Cerdyn Teithio Rhatach’.

“swashbuckling, risk-taking, outward looking, multi-lingual”

The collection ends with a handful of poems in both Welsh and English by Ifor ap Glyn. In ‘How to Drink Matango’, he toasts the friendship of the three Molas – a word roughly equivalent to ‘uncle’ that is an oft-used mark of respect – by singing a beatitude: ‘Blessed are the poets from Wales / for they shall experience matango / the palm tree’s daily god-send.’

It is a touching portrait of the ‘drinking and parley’ that ‘extends the afternoon’, a fellowship that cements the bond between the three poets and two countries.

In ‘A Traditional Poem of Thanks for a Shirt’ ap Glyn brings the traditions of cywydd, a Welsh metrical form that dates back to the fourteenth century, to bear upon contemporary Cameroon.

In so doing makes Iya Efeti, Eric’s mother, a kind of heroine; her gifting of a shirt befitting of Joseph (pictured next to the poem) is compared to Guto’r Glyn’s fifteenth century thanks for a purse to Rhisiart Cyffin through that famous phrase ‘Never in the island of Britain’.

There are some obvious flaws in the book’s production – some low-res photographs and the odd howler of a typo that betray enthusiastic editorial haste – but this is a brave publishing venture.

Innovative. Informed. Independent.

Your support can help us make Wales better.

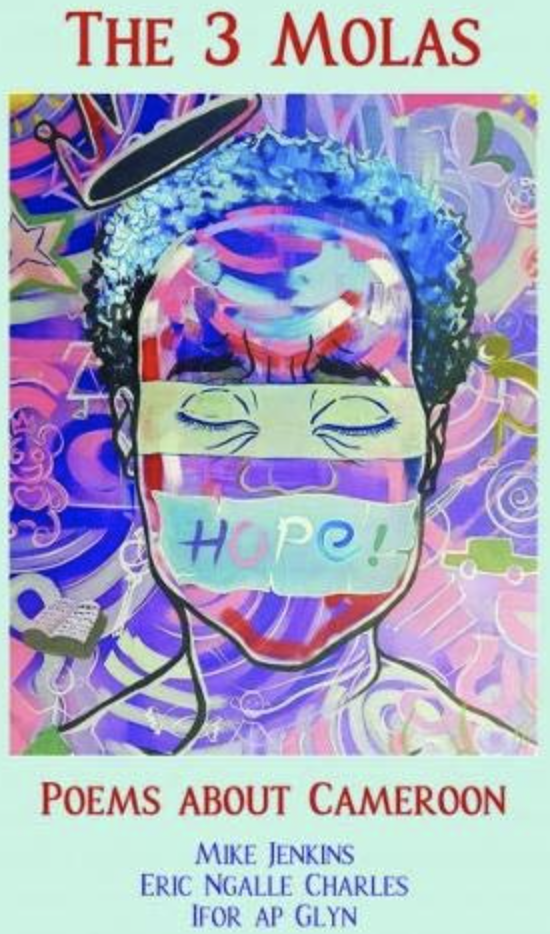

Its cover image, ‘Hope’ by Peter Lyonga is a powerful and mysterious painting; a man with closed lids gagged by ‘Hope!’ On the back cover, its publisher’s proud use of y ddraig goch and the unequivocal statement ‘Made in Wales’ make it a great advert for our nation as the book makes the inevitable journey south to Cameroon where it will be met with joy, wonder and the warmth of gratitude.

In a time when arts bodies are under increased scrutiny around how funds are actually used to support artistic endeavours rather than functionaries in offices endlessly shuffling pots of money about, Wales Arts International need to be commended for supporting The 3 Molas (Gwasg Carreg Gwalch).

It is their brand of poetry we will need – swashbuckling, risk-taking, outward looking, multi-lingual – that we will need more than ever as we emerge from the global pandemic that ironically brings us together even as it keeps us apart. Ap Glyn’s concluding lines are as apt as any in summarising this spirit: ‘let’s Cameroon-ize Wales for all we’re worth’.

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer.