Leanne Wood calls for an informed debate about extending the vote to prisoners

Today, the Equality, Local Government and Communities (ELGC) Committee publishes its report on prisoner voting. We recommend that the franchise be extended to prisoners serving terms of up to four years. Our committee took evidence from a range of experts including prisoners themselves, and we have spent hours considering the advantages and disadvantages of extending the franchise.

I also used to work as a probation officer. Part of our work, as part of the rehabilitation process and ensuring that the person’s risk of reoffending was reduced, was working to increase or even instil a sense of citizenship. Feeling included as part of the society and community is an essential element of that rehabilitation process. That said, I also favour extending the vote to prisoners because of the strong correlation between imprisonment and deprivation. The areas in Wales that are most deprived are more likely to have a higher proportion of their population in prison. Therefore a blanket ban on prisoner voting disproportionately affects deprived communities.

What do we mean by deprivation?

The Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD) defines deprivation as “the lack of access to opportunities and resources which we might expect in our society”. WIMD includes eight separate indicators of deprivation, which include income, employment, health, education, access to services, community safety, housing, and physical environment. Because the WIMD does not provide an overall ranking of deprivation by local authority, deprivation levels are calculated by the overall number of Lower Super Output Areas (LSOAs) per local authority area.

What is the link between deprivation and social exclusion?

There is a very clear link between poverty and social exclusion. The Social Exclusion Unit’s 2002 report, Reducing Reoffending by Ex-prisoners, stated: “before they ever come into contact with the prison system, most prisoners have a history of social exclusion, including high levels of family educational and health disadvantage, and poor prospects in the labour market.”

The Social Exclusion Unit also reported a strong correlation between poverty and unemployment, truancy, drug use, lower literacy, mental ill-health, and poorer access to education and healthcare, among other measures. We also know that there is a strong correlation between social exclusion itself and levels of imprisonment.

What is the link between deprivation and imprisonment?

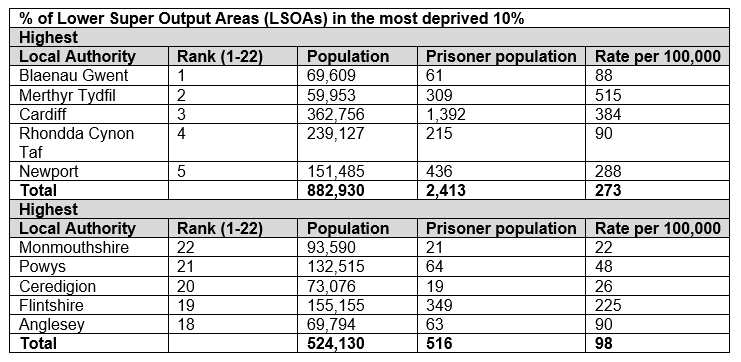

Ongoing research by the Wales Governance Centre indicates that “although less than a third (28%) of Wales’ population live in Blaenau Gwent, Merthyr Tydfil, Cardiff, Rhondda Cynon Taf, and Newport, almost half (49%) of all Welsh prisoners recorded a ‘home address’ in these areas.” These five local authority areas have the highest percentage of LSOAs in Wales, compared to Monmouthshire, Powys, Ceredigion, Flintshire and Anglesey, which have the lowest percentage.

The Wales Governance Centre states that “combined imprisonment rate for the five local authorities with the highest percentage of LSOAs in the most deprived 10%” is 2.8 times greater than the five with the lowest percentage of LSOAs in the most deprived 10%. People in Wales who live in relative deprivation are almost three times as likely to be imprisoned than those who live in Wales’ least deprived communities.

The social justice argument for extending the franchise

By enforcing an out-dated blanket ban on prisoner voting some of our most deprived communities are being put at a double disadvantage. These communities already experience some of the highest levels of social exclusion in Wales. They already experience some of the highest levels of unemployment, the lowest literacy levels, the worst mental and physical ill-health, as well as barriers to education and healthcare. Now we know that they are also far more likely to be imprisoned.

If we continue along this road, we accept that people from some of Wales’ most deprived communities should simply shut up and put up with their deprivation, as though it were inevitable. Or we could make it easier for them to lead law-abiding lives. Nothing is inevitable. Poverty and deprivation are structural and societal, the result of political choices, which means that there are ways to turn things around. To lose your right to vote is another way to socially exclude a person or a group of people.

And when the empirical research tell us that there is a strong correlation between social exclusion and deprivation, and thus between deprivation and imprisonment, it makes no logical sense to me that we should continue to enforce a blanket ban on prisoner voting. To do so is to say that we are content to place a double burden on some of our most deprived communities; to say to them that we are happy for them to be almost three times as likely to be imprisoned, and then that we’re going to make it even more difficult for them to be included back into society.

We should be doing whatever we can to break down those barriers and ensure that no one else has to live in inevitable poverty. And if through this we can reduce the chances of people committing further offences, then we would be meeting the needs of victims of crime as well – surely that has to be our ultimate aim?

I am pleased to put my name to this report and set of recommendations from the ELGC Committee. I’m very much hoping we can have a sensible and rational debate about this – it’s long overdue.

All articles published on Click on Wales are subject to IWA’s disclaimer